Targets in Czech Digital Covid-related Humour

Masks, disinfection bottles and medical workers dressed in spacesuit-like protective clothing. We have grown used to seeing these images on our TV screens as well as out there in the streets when we leave our homes and walk past a Covid testing point. By now, they have become a part of our everyday lives, but when they first started appearing on Czech TV screens, in March 2020 together with the announcements of the first government measures, they felt very alien and terrifying. I still remember how scared and threatened most of my friends and family members felt. And yet, we managed to laugh in that situation: when watching the news with my family, at the sight of the protective suits and recommendations to protect our health somebody said they’d consider wearing such spacesuit-like medical clothing next time they go down to the shop because at least they’d finally get a chance to feel like an astronaut. Despite understanding the gravity of the situation, the rest of the family and I giggled at that remark. It helped us relieve the tension and deal with anxiety at that moment.

Since then, we’ve exchanged many jokes and funny remarks about the pandemic; as well as many other people we’ve also used social media to share texts and images we considered funny with each other. We laughed together and felt, at least for a while, that the situation might not be so severe. This is what humour can do: work as a coping mechanism as well as align people. However, among the humorous material we’ve exchanged and seen, there are also instances which not everybody found funny, instances which are offensive to some people even though for others they are humorous. With many jokes and memes, whether I laugh or feel offended depends on who I identify with – whether with the butt of the joke or those who differ from it. Humour is not only capable of uniting people but also of dividing and antagonizing them. Although people around the world, irrespective of their social status, nationality or opinions, have all been in the same boat having to face the virus, the humour they have been using not only creates unity and lets them cope with and fight the crisis together, but it also creates in-groups and out-groups among people and allows them to fight and mock each other.

Dimensions of humour and targets

Reacting to such a disastrous event as the pandemic by using humour is an inherent part of human nature, because, as mentioned, humour works as a “coping mechanism”[1] and helps people mitigate the negative emotions evoked by the crisis. However, the function of humour is not only to bring relief, its role is explained for example also by superiority theory, which addresses the use of humour to express triumph over the errors or misfortune of others[2]. The multifaceted nature of humour can also be approached by distinguishing between so-called dimensions of humour. The dimensions of humour which scholars traditionally recognize are primarily the affiliative and aggressive dimensions, accompanied by self-enhancing and self-deprecating dimensions, which are targeted at the self[3]. Affiliative humour is described as humour that everybody can laugh at, that unites people, that is tolerant of others and creates a bond between people. In contrast, aggressive humour divides people[4] and typically includes a “target“, which is the “butt of the joke” that is insulted and mocked[5]. In self-enhancing and self-deprecating humour, the target is the “self”, i.e. the teller of the joke or the creator of the meme. The difference between these two self-targeting dimensions is that self-enhancing humour expresses a positive attitude, the teller/creator sees themselves in a positive light, whereas self-deprecating humour degrades the self and stresses the “poor me” quality.

The presence of targets is traditionally associated with aggressive humour. However, these four dimensions of humour are often not separated from each other, they overlap and more than one of them can be manifest in one humorous text. It can even be said that due to its inherent nature and function, humour in general is affiliative. This affiliative function, i.e. the capacity to bring people together, is typically also present in those humorous texts which can be interpreted as aggressive against somebody. In such humorous texts, a certain group of people is affiliated as it can laugh at and stand in opposition to another group, “the others”, who are the target that is mocked. Such a relationship corresponds to Van Dijk’s ideological square[6], as the relations between the actors represented in the humorous text are constructed as “us” vs. “them”. Negative features of “them” are stressed, exaggerated and parodied, and the positive ones are suppressed. At the same time, “we”, the in-group that laughs at the expense of the target, stand allied against “them”.

Exploring oppositional relationships in humorous discourse

In order to gain an insight into how humorous discourse in the Covid times is capable of constructing the unity of a group of people as well as oppositions between groups, advantage was taken of the use of digital tools. In the digital age it is easy to share humour with one another, to spread it and to let it circulate. People use social media, and nowadays especially meme formats dominate among the circulating humorous texts. The popular meme formats can not only be easily circulated, but also easily collected and thus serve as a suitable material for analysis. Therefore, humorous Covid-related material circulating among social media users in the Czech Republic was collected and analysed. This blogpost is based on an overview of humorous memes that have been circulating on social media platforms in the Czech Republic from the first appearance of the virus (December 2019) to February 2021.

The circulating meme material was solicited from friends, colleagues, university students and other social media users. In total, the Czech collection includes about 1000 memes that were circulating among users of Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp and more traditional e-mail. After collecting them, the memes were tagged in terms of their form, date of collection, topic, the “dimension” of humour they represent and the targets they include.

The aim of the analysis of the collected Czech Covid-related memes was to reveal the construction of oppositions of the in-group “who laughs” at the expense of the out-group, that is the targets, to understand what role of the targets in the pandemic situation the humorous discourse constructs, and what general discourse strategies are reflected.

Infobox – memes

Internet memes are “images and videos that share common characteristics, are distributed online by numerous participants, and are created with awareness of other images and videos”[7]. They are digital objects produced and disseminated by their creator, but often are transformed by the transmission of many other users through the Internet. They are shared by members of the digital culture often for the purpose of parody, satire or critique. Important is especially their element of intertextuality and the fact that not only the meme creators, but also their distributors and re-posters contribute to their reconstructing. Most often they are multimodal, with a visual image constructing meaning through visual grammar, and a textual part.

Local context

As any discourse is action, Covid-related humorous discourse is also set in a context and cultural background the knowledge of which is crucial to be able to interpret the humorous texts. The first cases of people infected with the new coronavirus in the Czech Republic were reported on 1 March 2020[8]. However, Czech people had been following and responding to the presence of the virus since its first occurrence. Even before March 2020, humorous texts were appearing in the country as a response to the mediatized disaster, perceived rather as “distant suffering”[9] of other nations at that time. When the threat of the disease became more imminent, Czech people were no longer just spectators of a crisis happening somewhere else, but they needed to resolve and cope with a situation that suddenly concerned them directly. Therefore, the number of humorous items also rose considerably, and their topics changed from relating just to the “other” and “distant” to relating also to “our area” and “our everyday lives”. Czech digital humour has since then reflected the topics which are shared across cultures – mask wearing obligatory for all, lockdown, social distancing, etc. However, there have also been topics of a more “critical” nature. As the virus has been around for a long time, what people have felt have not only been worries for their own health and puzzlement over the new situation, but also dissatisfaction with the regulations imposed by the government, frustration and anger. Many Czech people started to perceive the regulations aggrievedly as baseless restrictions on their freedom, which also reflects in the circulating humour. The leading figures of the state – the president and his spokesperson, the prime minister and some political party leaders with controversial opinions and scandals, had already been criticised by many even before the pandemic. After the start of the pandemic, they were, on top of that, held accountable for the unpopular decisions impacting the lives of every citizen. It is also important to stress that in the Czech Republic, there was a tremendous difference between how the country handled the pandemic situation in spring 2020 and how it coped with it approximately a year later. In spring 2020, it indeed seemed that the country succeeded in slowing down the spread of the infection. About a year later, on 24 February 2021, Czech media reported that the country had the highest numbers of infections worldwide. However, even the favourable situation in spring 2020 was not perceived as the government’s doing. In contrast, Czech society blamed the government for its incompetence from the very beginning of the pandemic and has not stopped since. What the humour does not forget to mirror is also the instability of some of the prominent figures. For instance, between December 2020 and April 2021, the country had 4 different ministers of health and at the time of writing, the latest one is to be replaced by the original minister of health in December 2021. These replacements and resignations from the office were perceived by many as another sign of the weakness and incapacity of politicians and thus also contributed to making them easy targets of the humorous texts.

Selected memes illustrating the construction of in-group/out-group oppositions

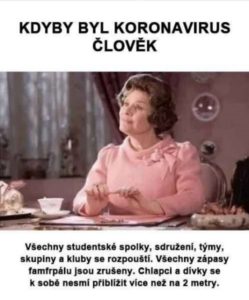

© forwarded by a WhatsApp user, author could not be traced

Translation Meme 1:

IF CORONAVIRUS WERE A PERSON

All student clubs, associations, teams and group are dissolved. All Quidditch matches are cancelled. Boys and girls must not approach each other closer than 2 metres.

The memes 1–5 above are examples of humorous texts shared by social media users in the Czech Republic in the period from December 2019 to February 2021. An overview followed by discussion of them in the following section, illustrates the ability of humorous discourse to construct in-group/out-group oppositions and align as well as antagonize social groups.

Meme 1 uses an intertextual reference to the unpopular character Dolores Umbridge from the Harry Potter films and a conditional in the headline “If the coronavirus were a person” to embody the virus. Then it goes on to name the restrictions which are imposed on “us”, the people. Here, the virus itself is targeted and blamed for all the restrictions people are under. It could thus serve as an example of humour uniting people, humour of a purely affiliative nature.

© forwarded by an Instagram user, author TMBK, © TMBK

Translation Meme 2: “And this is far from all, together with this restriction you’ll get one more for free.”

However, in memes 2–5, it is not the virus that is targeted but an opposition of one group of people against another constructed. Meme 2 refers to Horst Fuchs’s teleshopping programmes, however, the faces of Horst Fuchs and his assistant are changed for the faces of the then Czech minister of health and the Czech prime minister, respectively. The collage refers to the perceived amateurism of those two figures in authority and the increasing number of restrictions which the government imposed at the time of the occurrence of this humorous sample. Compared to Meme 1, this time it is not the virus that is held accountable and blamed for the restrictions and discomfort, it is the politicians. This meme is an example of a very strong tendency found in the collected material to target authorities. The construction of oppositions based on the attitude to political decisions then also permeates humorous material in which the representatives of the government are not explicitly present.

© forwarded by an Instagram user, author TMBK, © TMBK

Meme 3 illustrates another notable tendency: targeting other nations and constructing the targets as those to blame for spreading the disease. As purely visual material, it depicts the South Korean director Bong Joon-ho blowing his nose or covering his face with a tissue while accepting the Academy Award. The audience in the theatre reacts with a stampede in fear of getting infected. Meme 3 targets Asian people as those who spread the infection. Bong Joon-ho is here not targeted as an individual, but as a representative and symbol of a much bigger group of people, here even exceeding a nation.

© forwarded by an Instagram user, author TMBK, © TMBK

Translation Meme 4:

“I will not get vaccinated, I wouldn’t like to become infertile or get cancer.”

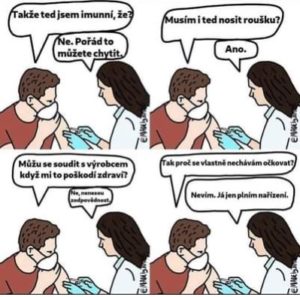

© forwarded by a Facebook user, author could not be traced

Translation Meme 5:

“So now I am immune, right?

- No, you can still catch it.

Do I have to wear a mask now?

- Yes

Can I take the manufacturer to court if they harm my health?

- No, they are not accountable.

So why am I getting vaccinated at all?

- I don’t know. I’m just obeying the regulations.

Finally, Memes 4 and 5 illustrate the antagonism between groups even within one nation. Meme 4 targets those who refuse vaccination by ridiculing their arguments. (The visual image with text shows a smoker arguing that she will not get vaccinated due to her fear of infertility or cancer. However, infertility and cancer are scientifically proven consequences of smoking, whereas as consequences of vaccination they are only speculated about by anti-vaxxers and often mentioned in their discourses.) Meme 5, on the contrary, targets supporters of vaccination. (The visual image with text shows a discussion between a doctor and a person getting the jab. The doctor cannot confirm any assumed advantages of vaccination, such as complete immunity, etc., and reveals she does not know any reason why to get vaccinated other than obeying the regulations). These two examples illustrate the strong division of opinions within society.

Politicians as targets and oppositions within the nation based on authority obedience

Meme 2 above illustrates the strong tendency of targeting the authorities and government representatives. The role of politicians in the humorous memes is predominantly constructed as that of “imposing too many or illogical restrictions” (as in Meme 2, on securitization cf. the contribution by Elena Dück), or, contrarily as “failing to act whatsoever” and leaving their citizens to twist in the wind. This was pronounced, e.g., in the period when there were not enough protective masks, which led people to sew them at home. In such memes where politicians and government representatives are targeted, the antagonism is based on the opposition of ordinary citizens affiliated to the elite.

The relationship towards the elite also permeates, however, memes in which the elite are not explicitly present and in which in-group/out-group opposition is constructed between ordinary citizens within the nation. Oppositions between fellow citizens reflect the strong division of opinions in society on some matters related to the pandemic, such as mask-wearing or vaccination: there are humorous memes which target both supporters and opponents of a certain position. The connection to the groups’ position in the political environment is notable: the target is often mocked for either obeying or disobeying government advice. Targets obeying the advice and regulations (e.g., people wearing masks, people supporting vaccination as also in Meme 5 above) are typically depicted as sheeples that blindly follow the authorities and do what they are told. Constructing the targets as sheeples that blindly follow the authorities stems from the same ideological motivation as targeting and opposing the government and criticising them for imposing restrictions. The in-group (the meme creator and anybody who identifies with their position and is able to laugh at the target) disagrees with the government and feels the need to resist them. The in-group perceives them as the “other” that needs to be opposed. Hence, those who do not oppose the government with the in-group are perceived by the in-group as allies of the “other” and thus become the “other” as well.

On the other hand, people disobeying the advice and regulations are also targeted (e.g., people not wearing masks, people violating the quarantine rules, people refusing vaccination as also in Meme 4 above). Such construction is aligned with the discourse of responsibility which is used by the authorities in order to justify the measures and regulations. The targets in such memes are typically portrayed as irresponsible and as a threat. They are mocked because the in-group fears they could spread the infection and uses them as an easy target that can be blamed if the pandemic situation does not improve.

Other nations as targets and targets with no specific role in the pandemic

Constructing the target as a threat is also found in memes that create in-group/out-group oppositions between different nations (as also in Meme 3 above). The in-group affiliates the Czech people who laugh at another nation, which is typically represented by a person read as belonging to it due to their physical features. The nation is also sometimes represented by an object stereotypically perceived as characteristic of it (e.g., Italy targeted through the depiction of a pizza with the virus on it). The other nations in the collected memes tend to be blamed for spreading the virus and depicted as the guilty party who the in-group prefers to avoid in order to protect itself. This is often connected to the discourse ostracizing other nationalities and built on prejudices against them. Besides this, humour targeting other nations also shows a tendency to construct the relationship of rivalry between nations, mocking those which at the specific moment have a higher number of infected people compared to the home country.

However, there are also memes in the collection that target other nationalities or other groups of people not based on their specific role related to the pandemic or their opinions on and approaches to it. Other nationalities, minorities, groups of people delineated based on some of their characteristics (e.g., wives, elderly people, etc.) appear as targets in the meme collection even if no specific role related to the pandemic is constructed (e.g., Vietnamese minority targeted for their imperfect knowledge of the local language, etc.). They are positioned against the in-group due to socially and culturally rooted differences that existed even before the pandemic, and the Covid situation is represented in the memes as a background reality against which long-existing stereotypes about other nationalities, social groups, etc., still apply.

Humour as a double-edged sword reflecting social groups’ position in the political environment

The overview of dominant tendencies found in the Czech meme collection shows that humour corresponds to the mood in society and aligning, as well as oppositional discourses targeted against the elites, other nationalities or fellow citizens based on their position in the political environment (cf. Christiane Barnickel’s and Dorothea Horst’s literature review on Covid-19 and exclusion). The construction of targets exemplifies that humour is a double-edged sword that brings alleviation to some but at the same time can hurt others. It has both the affiliative and the aggressive function: it is capable of uniting all people into one huge in-group which fights the virus together (also with humour as a weapon), but equally the humorous discourse can be oppositional and capable of dividing people and constructing in-groups and out-groups. In those, “us” stand against “them” as the target of the humorous text. Such representation of opposing groups corresponds to Van Dijk’s ideological square as the out-group’s negative features are highlighted and ridiculed. The in-group that laughs at the expense of the out-group unites those who do not identify themselves with the target, who do not get offended by the humorous text and who consider themselves different from the target. It can also be argued that the representation of targets works as a tool for stressing the positive qualities of the in-group: the target is ridiculed for their specific approach to the pandemic situation, the in-group does not feel offended by the humour because they do not identify themselves with the target, therefore, the discursive situation can be interpreted also as self-praise for the in-group for being different from the target.

The humour discourse confirms and reinforces the construction of oppositions between social groups that exist universally and apply also outside the pandemic situation: there are out-groups identified in the humorous material that are targeted based on their long-standing differences from the in-group which have not emerged with the pandemic but just still hold against its background. However, what predominates in the collected humorous material is the construction of targets which are ridiculed for their specific role in or approach to the pandemic situations. Targets are mocked based on how they handle the regulations, whether they come from an area with a high number of infections, etc. Specifically, as shown above, frequent targets are found to be politicians, nations with a high number of infections and groups of fellow-citizens who have different opinions related to the government regulations and protective measures. A very strong strategy of the construction of such targets’ role in the pandemic situation is that of blaming them for the spread of the virus or for the uncomfortable restrictions, and holding them accountable. When the target is another nation or a citizen not following government regulations, they are also often constructed as a threat to the in-group. In the in-group/out-group dichotomies between different nations, expressions of cross-national comparison and rivalry can also be found.

Divisions within the nation between fellow-citizens are often based on the groups’ position in the political environment. A strong tendency is the construction of their approach to responsibility: those who, e.g., refuse to wear masks, get vaccinated, etc., are depicted as irresponsible, and thus the in-group as responsible. On the other hand, however, those who, e.g., agree to wear masks, get vaccinated, etc., are in other memes depicted as sheeples mindlessly doing what they are told by the authorities, and thus the in-group as independent and able to see through any potential government plots. The notion of responsibility thus changes depending on whether its advocates are positioned as the in-group or the target. The dichotomies between fellow-citizens also follow the pattern of oppositions between citizens and government representatives: the targeted government representatives and targeted citizens who follow government regulations will most likely share the in-group that opposes them, because if a government representative is perceived as an enemy figure that needs to be mocked, then those who obey them are considered their allies and need to be mocked as well.

These tendencies in humorous memes very well reflect the mood in Czech society and even allow us to observe different trends depending on what stage the pandemic situation was at when the humorous meme was created. However, it can be argued that they also demonstrate characteristics of pandemic discourse that are shared globally. The reflection of relationships between social actors and the construction of their image and role in the pandemic is expected to be shared transnationally. The particular role of humour in the pandemic discourse and the applicability of the findings from the Czech material to the global context is now being investigated also thanks to an international database of Covid-related humour initiated by Kuipers and Boukes[10]. The database, which is now under construction, gathers humorous contributions from various corners of the world, facilitating further analysis by scholars from various countries and disciplines. Therefore, it promises fascinating further research and space for intercultural comparisons.

[1] Samson, A. & Gross, J. (2012). Humor as emotion regulation: The differential consequences of negative versus positive humor. Cognition and Emotion, 26, 375-384.

[2] Martin, R., & Ford, T. (2018). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. Academic Press.

[3] Martin, R., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., Gray, J. & Weir, K. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality. 37, 48-75.

[4] Meyer, J. (2000). Humor as a Double‐Edged Sword: Four Functions of Humor in Communication. Communication Theory. 10, 310-331.

[5] Attardo, S. (Ed.) (2017). The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor. Routledge Handbooks Online.

[6] Van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Critical Discourse Analysis. In D. Tannen, D. Schiffrin & H. Hamilton (Eds.), Handbook of Discourse Analysis. (pp. 352-371). Blackwell.

[7] Jensen, M. S., Neumayer, C. & Rossi, L. (2020). ‘Brussels will Land on its Feet like a Cat’: Motivations for Memefying #Brusselslockdown. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 59–75.

[8] V České republice jsou první tři potvrzené případy nákazy koronavirem (2020, March 1). Ministerstvo zdravotnictví České republiky (MZČR). https://www.novinky.cz/koronavirus/clanek/cesko-je-na-tom-s-covidem-opet-nejhur-na-svete-40351902

[9] Chouliaraki, L. (2006). The Spectatorship of Suffering. SAGE Publications Ltd.

[10] Boukes, M. (2020, April 6). Research into ‘corona humour’. University of Amsterdam. https://www.uva.nl/en/shared-content/faculteiten/en/faculteit-der-maatschappij-en-gedragswetenschappen/news/2020/04/corona-humour.html

How to cite this blog post:

Žákovská, Iveta (2022), “Targets in Czech Digital Covid-related Humour”, Crisis Discourse Blog (CriDis), URL = https://www.crisis-discourse.net/de/2022/06/targets-in-czech-digital-covid-related-humour/.